It is a hard time to be a skeptic about Artificial Intelligence (A.I.) or to give it its more proper title in its current iteration: Machine Learning. What do I mean by hard time? Well, there are plenty who accuse those who do not wholly embrace A.I. tools as being modern Luddites, people against any kind of progress (that is a slanderous gross misinterpretation of the position the Luddites held, but I digress…). Just look at the stock market and all the money pouring into A.I. research say the true believers. For those who have never heard of a bubble; I have a bridge to sell you.

Then we could ask, what do I mean by skeptic? This is a surprisingly nuanced question when it comes to Machine Learning. I believe Machine Learning can do some interesting and useful things in our world. However, I do not believe that we are in any way asking the right questions or placing the right guardrails to protect those without whom these machine learning tools would not exist. I’m talking about those whose work is used to train A.I., are given no credit, and stand to suffer the most from a race to the bottom to find a machine that can do a good enough job to replace a costly human and make someone else a billionaire. I’m not a skeptic about Machine Learning. I am skeptical about people and our seemingly limitless capacity to exploit any opportunity, disguise it as something else, and then abdicate any responsibility for the consequences.

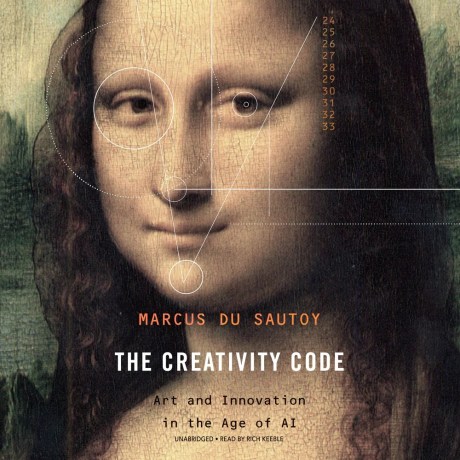

Mathematician Marcus Du Sautoy in an entertaining book, The Creativity Code: Art and Innovation in the Age of AI, acts as a proponent of Machine Learning. At the same time the author is having a self-confessed existential crisis over whether he is being put out of a job as a mathematician by A.I. Ultimately, the book fails due to the author’s lack of an ethical framework for this discussion. Written in 2019, that’s before the days of Chat GPT kiddies, Mr. Du Sautoy uses Eva Lovelace as a jumping off point for his existential exploration of all things Machine Learning.

Eva Lovelace, born in 1815, was an English writer and mathematician and is frequently called the first computer programmer. She was also a colleague of Charles Babbage, the inventor of the Difference Engine and proposer of its follow up the Analytical Engine. It is Lovelace who is credited with the intellectual leap of understanding that the Analytical Engine was not just a calculation machine. That once a machine understood numbers it could be applied to all sorts of subjects where numbers could take the place of other values. She is also famously known for a quote seeming to pour scorn on A.I.

“The Analytical Engine has no pretensions whatever to originate anything. It can do whatever we know how to order it to perform. It can follow analysis; but it has no power of anticipating any analytical relations or truths.”

Mr. Du Sautoy ultimately believes that Ada Lovelace was mistaken, but I feel this is more down to interpretation rather than to clinical facts. What the author does rightly acknowledge is that data is the fuel of A.I. That access to data will probably be the oil of the 21st century. Where he fails is in not grappling with the consequences of data as fuel and its ethical ramifications. “Don’t worry about all those people in the Middle East, they don’t matter considering all that oil that’s right under their feet,” the writer seems to be saying.

In the Creativity Code, there is some interesting exploration of how the use of algorithms is teaching us about how humans think about subjects and how we go about creativity. To unlock the human algorithm. It is particularly insightful to recognize that the creative leap is not to create new things, but to recognize when one of those new things may have value to others.

While Mr. Du Sautoy worries about his own profession, he is all to ready to write off whole armies of other creative people because he does not consider the work they do to have value. Whether that is to write business articles or reports, or to write background royalty free music. He fails to realize that it is this “bread and butter” creative work that allows writers and composers to work on projects more dear to their hearts. The author seems to believe that this “drudge work” is holding them back from doing more interesting things. No, it’s the money these creatives charge that has an impact on the bottom line and Machine Learning is cheaper. These creative people will not have more time for more interesting work. They will be unemployed. That the previous work of the creatives is used by machine learning as part of its training data, its fuel, is of course just salt in the wound.

Indeed, Mr. Du Sautoy blithely admits that he asked a Machine Learning tool to write a section of the book for him. In a fit of worry about plagiarism, he hunts down an almost identical article on the internet – but then keeps it in the book saying; “if I get sued for plagiarism, we can then agree that this is a bad idea.”

This book probably suffers from being a book of its time, before there was seemingly endless hype and not enough skepticism surrounding Machine learning. And it is such a shame as the book is genuinely entertaining. The section on the game Go in particular raises some interesting questions. However, the lack of ethical awareness is unforgivable and tarnishes this otherwise interesting and entertaining volume.