What comes to mind when you think of the term “Luddite?”

For the more historically minded of you it might be that they were a British 19th-century grass roots movement that were opposed to, and smashed, technology due to losing their jobs at the start of the industrial revolution.

More usually, “Luddite” is used as an epithet to describe someone who refuses to embrace change, usually technological, or insists on doing things the hard way when a simple technological solution exists. Reactionary idiots who were doomed and dumb. Malcontent losers.

These are both corruptions that were deliberately foisted on the public by those who had the most to gain by discrediting the movement: the State and the “big tech” entrepreneurs of their day.

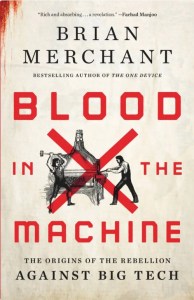

In “Blood in the Machine: The Origins of the Rebellion Against Big Tech” Brian Merchant does a most remarkable thing for a book on a historical subject. He places events from the beginning of the 1800s in context with the events of today and the same challenges we currently face when it comes to technology and work.

The first half of the book is a history of the Luddite rebellion. Its early beginnings with workers refusing to cooperate with inventors on the design of machinery that was clearly created to put them out of work, to civil disobedience and protest, and then ultimately to the very brink of civil war. While the first half of the book does occasionally highlight just how close some the challenges that 19th century weavers were facing are to modern day concerns, it is the second half of the book which focuses on the “gig economy,” A.I., and other forms of modern automation.

What becomes clear throughout the book is that the Luddites were not sheep afraid of change. This was a nuanced, decentralized movement that had clear goals and wanted to embrace technology and change, but wanted their needs and livelihoods taken into consideration. Weavers were artisans who worked for themselves, setting their own hours, and involving the whole family in their work – but on their own terms. The industrialized mills that replaced them employed mostly woman and children working long hours for low pay and producing a lower quality product that was “good enough.”

A theme that crops up both in the 19th century section and the 21st century section is the concept of the replacement of skilled workers with cheaper lower skilled workers. Mr. Merchant also spotlights the outsized role that venture capitalists play in this dynamic – financing a cheaper alternative to one industry to the point of bankruptcy and then either raising prices or lowering wages of those now forced to work for the bright and shiny new thing: Uber and Lyft I’m looking at you.

The Luddites were met with brutal resistance. Factories became fortresses and soldiers were based in every northern town. This was a time when Britain was in a deeply unpopular War with France and was losing its American colonies. Dozens of Luddites were hanged, mostly for the breaking of machinery, and those who took the Luddite oath were often transported to Australia – a life sentence at the time. All for opposing profit over people.

While not only warning of the impact that disruptive change, both in the past and the present day, the author also adds the note of caution about how people are already pushing back against the same type of change as the Luddites fought against over two centuries previously. The strikes, organizing, and protests by Uber and Lyft drivers to be considered employees rather than contract workers. The organizing at Amazon during COVID-19 over safety concerns. The Hollywood writers strike over using A.I. technology.

These are not isolated incidents.

They form a pattern of how technology is often imposed on people without thought as to its impact. That the technology that is supposed to alleviate work often just degrades it. Just the lexicon of Silicon Valley points to this: “disruption,” “move fast and break things,” “Revolutionize.” To ignore these warning signs could quite possibly doom us to repeat the mistakes of the past.

There is often, from both Hollywood and the media, a hysteria that “the robots are coming for your job.” As Brian Merchant points out; the robots are not coming for anything. It is the people who run companies and implement technologies that decide the impact they will have on peoples’ jobs, and ultimately their lives. This needs to be a discussion, separate from the also highly needed discussion on how machine learning is trained, and how venture capital distorts the business landscape. All these discussions are related, but we have real choices ahead that we will all need to make.

It is interesting to reflect on what might have been if the Luddites had won. There would still have been an industrial revolution, but perhaps the assumed antagonistic relationship stances between management and employees, whether real or perceived, might have had a very different starting point. We can’t change what happened to the Luddites, but we have all the indicators that we have an opportunity ahead of us now.

This is a book for our times and a warning about one possible future.